I Never Had The Chance To Meet Jackie Robinson

I was lucky enough to have met and interviewed many Hall of Famers including Joe DiMaggio, Hank Greenberg, Ted Williams and Stan Musial.

I also had the chance to meet and gab with many of the stars from the old Negro Leagues who went on to play in the major leagues after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier – Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin and Satchel Paige. But I never had the chance to meet Jackie Robinson.

I did, though, meet Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s elegant, graceful widow.

From everything I’ve heard on the baseball beat, Jackie Robinson was a credit to his race – the human race. More important than being a great athlete and ballplayer, he was intelligent, articulate, and above all a great husband and father. He was, in short, a genuine mensch.

Robinson was only 53 when he died in 1972, old before his time, racked with diabetes and nearly blind.

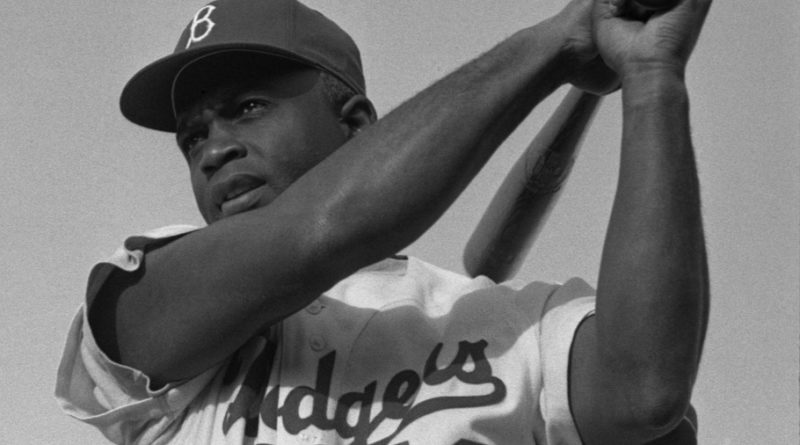

This year baseball is celebrating the 65th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s breaking the color barrier. It was April 15, 1947, when Robinson became the first openly black man to play in the major leagues.

Ebbets Field was a ballpark of small dimensions and limited seating capacity of some 32,000. Only 25,623 paid their way in to see Robinson’s debut on Opening Day in 1947, 4,000 less than the ’46 opener. But the Dodgers went on to set their all-time Brooklyn attendance record of 1.8 million in 1947.

The only black man in the majors excited fans that year by batting .297 with 12 home runs and 29 stolen bases, more than double anyone else.

Calling the games on radio that year for Brooklyn was Red Barber, a man steeped in the prejudices of his era and place of birth. Barber was born in Mississippi and moved with his family when he was 10 to central Florida.

“I saw black men tarred and feathered by the Ku Klux Klan…. I had grown up in a completely segregated world,” Barber recalled in his book 1947 – When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball.

Barber thought about quitting. After all, a Southern gentleman in 1947 couldn’t be expected to work for an organization that would treat a black man as an equal. But Robinson wasn’t an equal – he was superior to most ballplayers at the time, superior as a player and as a man.

Robinson went to college and starred at UCLA in basketball and football before serving in the army. He earned the rank of second lieutenant and was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, and Fort Hood, Texas, where white officers wouldn’t give him a chance to try out for the baseball team.

After being turned in by a bus driver to military police for refusing to sit in the rear seating area, Robinson faced a court martial for disobedience but eloquently won his case. After receiving an honorable discharge, and with the doors closed to blacks in many fields including professional baseball, Robinson joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues in 1945.

Fair-minded men at the time tried to promote the integration of blacks in baseball without success. Boston Jewish councilman Isidore Muchnick threatened to pass legislation to ban Sunday baseball in Boston unless the Red Sox granted a tryout to three Negro Leaguers.

A tryout was arranged for three players from different Negro League teams – Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe and Marvin Williams.

The tryout was originally scheduled for April 12, 1945, but that turned out to be the day President Roosevelt died. Vice President Truman was inaugurated as president and Roosevelt was buried in Hyde Park, New York, on Sunday, April 15. The day of FDR’s burial, British forces liberated the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp where 16-year-old Anne Frank died the previous month.

The following day, April 16, the three Negro Leaguers came to their Red Sox tryout at Fenway Park. Jackie Robinson was the most impressive of the tryout trio, prompting Red Sox manager Joe Cronin to tell Muchnick he hoped the team would sign Robinson. But the Red Sox never followed up and would become the last major league team to field a black player – some 14 years later.

Robinson went on to star for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1945 and attracted the attention of Brooklyn Dodgers boss Branch Rickey, who followed Robinson’s activities off the field as well. Rickey was convinced he had found the right man to break baseball’s unwritten color barrier and signed Robinson to a contract in early 1946 and assigned the infielder to the Dodgers’ top minor league club in Montreal.

Red Barber was also following Robinson’s progress. It was just a matter of time before Robinson would be up with the Dodgers and Barber was mulling over quitting.

“I didn’t quit,” Barber related in his book. “I made myself realize that I had no choice in the parents I was born to, no choice in the place of my birth or the time of it. I was born white just as a Negro was born black. I had been given a fortunate set of circumstances, none of which I had done anything to merit, and therefore I had best be careful about being puffed up over my color.”

Irwin Cohen: Author, columnist, and public speaker Irwin Cohen headed a national baseball publication for five years and worked for a major league team, becoming the first Orthodox Jew to earn a World Series ring. He can be reached in his suburban Detroit area dugout at irdav@sbcglobal.net.